Hey Ashers!

YA recommendations with lists, pictures, and frequent parentheticals.

Spoiler Rating: High

Finest Katie,

I read Nina LaCour’s Hold Still shortly after my friend Jeff died, and the book utterly wrecked me. So of course when I learned that LaCour had written a YA lesbian romance, I . . . well, okay. I let it sit in my TBR list for two years.

But now I’ve read it, and returned to tell you that you’d probably enjoy it more than I did.

![]()

The plot, in brief: our narrator Emi (a talented young production designer in Hollywood) and her best friend Charlotte discover that recently-deceased movie icon Clyde Jones has a secret (orphan) granddaughter named Ava, whom he’s left an unknown (but presumably enormous) sum of money to. They hunt Ava down, reveal her grandfather’s identity, and point her to her awaiting bank account. They also point her to an audition for a new movie Emi and Charlotte are working on.

So Ava ends up learning about her (deceased) family, becomes filthy rich, and lands the lead role in what’s expected to be a fairly big movie. She also—of course—gets the girl: Emi.

![]()

Emi — an eighteen-year-old infected with Hollywood’s movie-sickness.

Ava — an eighteen-year-old with a troubled and mysterious past. She ran away from her cold, lesbian-hating adoptive mother, Tracey, and is now trying to scrape together a new life for herself in Los Angeles.

Charlotte — Emi’s best friend and occasional co-worker. She’s eighteen, but approaches every situation with a sensible, seasoned, professional air that makes her seem twice her age.

Clyde Jones — iconic star of Hollywood’s old Western movies. Recently deceased. Publicly known to be a bachelor, but secretly the father of Ava’s (long deceased) mother, Caroline.

![]()

A Slow-Growing, Lesbian Romance!

Need I say more? No. No, I don’t.

Actually, I will say more. It’s possible that Emi and/or Ava could be bisexual. Neither girl puts a label on her sexuality, and although both clearly state they like girls, both also admit to (rarely, potentially?) being attracted to a guy. So I’m tagging this book as both lesbian and bisexual, just to cover my bases.

A Biracial Narrator/Protagonist!

Emi’s race is barely remarked on, but what we did see made me so happy. Like so:

The book also briefly highlights how Emi’s (upper-middle class) family’s experience of and approach to their race compares to a homeless young black man’s experience and approach. I thought the comparison was both interesting and valuable, and wish the book devoted more than a couple pages to it.

Neat Details About Production Design!

Emi’s job entails designing movie sets: choosing the right furniture, rugs, plants, dishes, etc., then making the set look real. I loved watching Emi work, and seeing why she chose [these dishes] or [this wallpaper color] or [this couch] over the thousands of other [dishes/wallpaper color/couches] available.

For example: here, she’s spent seven weeks searching for just the right couch for a scene in which a teen character has sex for the first time (with a scumbag, the teen later realizes). She’s finally found the couch:

Love it.

Lesson: Life’s Not A Movie!

When Emi begins uncovering the truth of Ava’s grandparentage, she goes all Prodigy Production Designer and tries to craft a movie-style Tragedy-Turned-Triumph story for Ava. One of the first steps in her plan: introduce Ava to the fancy-pants hotel Marmont (which is thick with celebrities and celebrity-watchers).

But life—even Ava’s fairy-tale-esque life—isn’t a movie that Emi can manipulate.

Life is life, and it’s experienced in excruciating slowness and clarity, with no helpful foreshadowing of what lies ahead. People are not characters in movies, and their lives are beyond Emi’s creative control.

Hurray for narrators who learn interesting and important life lessons!

![]()

However.

I Was Bored

Okay, so this could be a problem with me rather than the book. I’m a fantasy reader, not a contemporary-romance reader.

My complaints, in brief:

- the writing style was emotionally distant,

- Emi’s self-absorption and entitlement pissed me off,

- the first hundred pages, in which Emi and Charlotte search for and locate Ava, bored me almost to tears,

- the story’s told from Emi’s point of view, so Ava’s (more interesting) story is only superficially shared with the reader,

- the movie they’re working on is the type I’d never watch: a quiet, contemporary piece about a lonely teen and a lonely adult who learn things about themselves through each other,

- we spend a lot of time watching them work on this movie, and good lord I don’t care.

What kept me reading, then? The fact that it was alesbian YA romance. Had it been a straight couple, I probably would have set it aside.

(Actually, I wouldn’t have picked it up in the first place.)

Emi’s Character Development

The story’s told in the first person perspective, from Emi’s point of view. Overall, the writing style (i.e., Emi’s inner monologue) is calm, clean, and reserved, leading me to assume that Emi is a calm-clean-reserved sort of person.

That is, until Emi describes herself (and her older brother Toby) thusly:

The energy-level bit threw me off. Calm-clean-reserved Emi had shown almost no energy, much less off-the-charts energy.

So I started paying closer attention to Emi’s behavior and narration, to see if that energy ever came through.

Did it? No.

I’m sorry, Emi, but you can’t just say “I have more energy than other people can handle” and then not follow through. As it stands, it looks like either you don’t know your own personality, or your author (who writes you with such a calm-clean-reserved voice) doesn’t. It’s impossible for me to bond with a narrator whose personality I never get a solid grasp of.

Whose Story Is This?

This book might’ve benefited from being told from both Emi and Ava’s perspectives.

Emi’s the narrator and protagonist (she learns important lessons about herself and life, and those lesson change her), but for most of the book, she has neither a real conflict nor an interesting goal.

It’s Ava who’s living the rags-to-riches story, with all its requisite complex emotions, internal conflict, internal and external changes. But we see almost none of those changes, and it’s unclear how (or if) she changes as a person as a result of her experiences.

I mean, sure, we see her trash her adoptive mom’s house while searching for her birth certificate; she cries while watching the movies that her deceased grandfather and deceased mother acted in; she has a brief, emotional confrontation with her adoptive mother (that doesn’t really resolve anything). But that’s about it.

It is so incredibly frustrating to be shackled to a rather boring character doing rather mundane things, while another character is enduring amazing struggles and major internal changes largely off-screen.

“But Liam,” you argue, “this book’s about how real lifeisn’t a fairy tale or a movie. If Ava—with her fairy-tale-esque metamorphosis from troubled homeless teen to happy wealthy starlet—were the narrator, that’d undermine the book’s message.”

Okay, fine. Maybe this is a flaw in me as a reader, and not a flaw in the book. And yes, it is neat to pair a “Life isn’t a movie” message with an Average Jane Narrator who’s watching from the sidelines while a Fairy-Tale Heroine’s life get turned upside down in Fairy-Tale Ways.

But I, personally, would rather get in on some of Fairy-Tale Heroine’s action—or, at the very least, have a more interesting Average Jane Narrator with genuinely interesting conflicts and goals of her own.

![]()

The world obviously needs more lesbian YA novels, and this certainly isn’t the worst lesbian book I’ve read to date. But it just wasn’t quite enough—emotional enough, intriguing enough, engaging enough, romantic enough, powerful enough—for me.

My search for a five-star lesbian YA novel continues.

Hugs,

Liam

1

1

Spoiler Rating, Overall: Low-Moderate

Spoiler Rating, Last Three Points: High

Best Ashers,

Unfortunately, Rebel of the Sands (which smooshes together the Old American West and an ambiguously-religioned Middle East) wasn’t the engrossing read I’d hoped for. I actually found it fairly dull, and riddled with silly plot points and shallow character development—but it had a spark in both its main characters and its basic concept that kept me reading, so three cheers for that.

I’ll try to minimize the spoilers throughout most of this critique, but be warned: there’ll be spoilers galore in the last three points in my Criticism section (“Pacing,” “Specific Plot Points” and “Amani-Related Things“). I’ll put another spoiler warning before I dive into them, don’t worry.

![]()

Mortals rule the desert nation of Miraji, but mythical beasts still roam the wild and remote areas, and rumor has it that somewhere, djinn still perform their magic. For humans, it’s an unforgiving place, especially if you’re poor, orphaned, or female.

Amani Al’Hiza is all three. She’s a gifted gunslinger with perfect aim, but she can’t shoot her way out of Dustwalk, the back-country town where she’s destined to wind up wed or dead.

Then she meets Jin, a rakish foreigner, in a shooting contest, and sees him as the perfect escape route. But though she’s spent years dreaming of leaving Dustwalk, she never imagined she’d gallop away on a mythical horse—or that it would take a foreign fugitive to show her the heart of the desert she thought she knew.

Rebel of the Sands reveals what happens when a dream deferred explodes—in the fires of rebellion, the smolder of romantic passion, and the all-consuming inferno of a girl finally, at long last, embracing her power.

I wish I had a map to show you. How on earth does this book not have a map?

![]()

Amani — a young Mirajin sharpshooter who’s all grit and sly commentary. Born and raised in Nowheretown, Death Desert, she has a desert kid’s outlook on life: (a) the weak die, and (b) you gotta look out for yourself.

Jin — a mysterious young man from the east, who takes pity on Amani and helps her begin her journey. He’s being hunted by the Mirajin Sultan’s army for an unspecified offense. (Possibly “unlawful hotness.”)

Prince Ahmed — the rebel prince, and rightful heir to his father’s throne. He has dreams of gender equality and racial equality and peaceful democracy (I guess?), and is scraping together a happy band of (mostly teenage) rebels to overthrow the Sultan and make it happen.

Commander Naguib — a young man in the Sultan’s army, whose primary goals in life are sneering the perfect sneer and spitting in Prince Ahmed’s face (preferably at the same time).

![]()

The Voice

The story’s narrated from Amani’s first-person perspective, and she starts out with a seriously strong narrative voice. Check this out:

Delightful as Amani’s voice is in the beginning, I got a little tired of it after a couple chapters, so I was relieved when the Old American West accent eased up without losing its vividness:

Sure, I would’ve preferred a perfectly consistent voice throughout, but I’ll applaud the book’s attempt at a strong voice nonetheless.

Amani and Jin

It’s not the most compelling romance I’ve ever read, but I did love the combination of Amani’s fierce “it’s me or the world, and I’m choosing me” attitude and Jin’s calmer “try not to do anything rash, but when you inevitably do, I’ll be there to help you out” perspective.

The Immortal Desert Horses

You won’t be surprised to hear that I loved the immortal desert horses—their creation myth, the process required to capture them, their abilities, all of it.

This is, um, a remarkably short praise section for a book I’m ultimately giving two stars.

![]()

I’d like to not ramble for hours, so let me just cover the most significant criticisms.

Cultural Blending

I’m not really comfortable with how the book blended a vaguely Middle Eastern culture with Old American West culture, for a few reasons:

- The book seemed to only use Middle Eastern-ish elements that (a) offered a dash of “exotic flavor” (some words and names, the mythology, etc.) or (b) portrayed Middle Eastern-ish culture in a terrible way (such as the horrifying misogyny, which leads towns to stone girls and women to death for any perceived sexual impurity). As far as I saw, the book doesn’t offer any other type of Middle Eastern-ish elements.

- On the other hand, the book’s Old American West elements were mostly there for the cool/badass factor: gunslinging, action scenes on speeding trains, run-down saloons, etc.

- No in-world explanation was given for how Middle Eastern-ish culture blended with Old American West culture, so I’m left to assume there is no in-world logic for it. The book needed a unique cultural blend to be cool and marketable, so it just chose these two particular cultures because, uh, they share a deserty climate, I guess?

Cultural blending can be really neat, but to do it well (and sensitively) requires a lot of care and world-building. This book, in my opinion, failed both the “do it well” and “do it sensitively” parts.

World-Building

And no, the world-building isn’t great either, as I immediately suspected upon seeing the heroine’s surname: Al’Hiza.

I’m not an Arabic speaker, but I know the apostrophe is the English notation of a specific letter—hamza, the glottal stop—and it has zero reason to be in Amani’s surname. The name should be spelled as either Al-Hiza or Al Hiza.

If no one bothered to research how to correctly spell the heroine’s own last name, it seemed likely that little/no research was done for the world-building, period. And yeah, my suspicion seemed justified. We have almost no grasp at all on Amani’s culture except that:

- some people pray at regular intervals throughout the day,

- women are treated like property/shit,

- racism is alive and well,

- they’re ruled by a tyrannical sultan.

Not exactly the elaborate world-building I’d have hoped for.

Amani’s Modern Attitude and Culturelessness

Now, I love a strong feminist heroine, but Amani’s particular expression of feminism felt out of place in her setting—like a 21st century teen punk rock feminist who time-traveled back several centuries and was dropped into a deeply misogynistic culture.

Her culture values a woman’s virginity, silence, and obedience over anything else she is capable of, and Amani consistently responds to this by holding up both middle fingers, shouting obscenities at the top of her lungs, then proceeding to do whatever the hell she wants.

I saw zero indication that Amani was connected to her own culture at all, which was really disappointing. Well-written characters should feel like products of their own societies and times, not like they were ripped out of a completely different world and plopped down into the story, like Amani was.

The Pacing

Good lord, the pacing was slow.

But first: spoiler warning! I won’t give major spoilers for the plot in this section, but if you don’t want to hear anything at all about the plot, skip the rest of this review and go straight down to the “In Closing” section.

VAGUE SPOILERS, AVERT THINE EYES.

Ready? Good.

Amani’s primary goal is to get the hell out of her hometown, Dustwalk. She succeeds about a quarter of the way into the book, and after that, she has no major goals.

Sure, she dreams of going to the capital city and living with her aunt (whom she’s never met or corresponded with), but she easily ditches that idea when she realizes Jin’s too hot to say goodbye to. And sure, she has a few (sometimes interesting) short-term goals, but for the most part she’s just . . . traveling. Taking life and its individual challenges as they come.

Jin, meanwhile, has a Super Secret Mission that he won’t tell Amani about. His secrecy and the mere fact that he’s trying to accomplish Unknown Things is a stark contrast to Amani’s goalless traveling. (Sound familiar?)

She doesn’t find out about the Super Secret Mission until a hundred pages before the end of the book—and then she doesn’t get actively involved in the Mission until sixty pages before the book ends. Sixty.

Specific Plot Points

SPOILER WARNING, TONS OF SIGNIFICANT SPOILERS AHEAD

This book had a lot of dumb plot points. For the sake of space and time, I’ll give you only two.

1. The Immortal Desert Horse

While she’s plotting her escape from Dustwalk, Amani captures an immortal desert horse that can travel significantly faster than a mortal horse. So does she ride it all the way to the big city (covering the distance in days instead of weeks), then sell it in the city for an exorbitant amount of money, and use that money to set herself up in her new home?

No. Of course not.

She rides it to the nearest little town with a train station, where she sells the horse for half what it’s worth, and buys a train ticket to the capital city. The train ticket is so expensive, by the way, that it almost bankrupts her.

Why did she make such a stupid decision?

The answer (oh god when will I get a chance to stop complaining about this) is because the story wouldn’t have worked if she’d ridden her magical horse straight to the capital. So the book made Amani dumb for the sake of months of boring desert travel and the opportunity for Amani to join Prince Ahmed’s rebellion. Great.

2. The Rebellion’s Plans

First, some background. Decades ago, when the current Sultan of Miraji was still just a prince, he turned to the vaguely French-ish kingdom of Galla for help overthrowing his father and placing himself on the throne. Galla agreed, so long as they could maintain a military presence in Miraji, and the new Sultan became their primary weapons supplier.

In the present, the Sultan wants to kick the Gallan military out of Miraji—but he also wants to avoid starting a war. So he’s started using his secret superweapon (that can burn whole cities to ash) against Gallan military garrisons, and blaming the Rebel Prince Ahmed for the destruction. The Sultan hopes to just . . . kill all the Gallan soldiers in his country, and then cross his fingers that the Gallan king doesn’t send more to replace them, I guess?

This is ridiculously dumb.

The rebels also want to kick the Gallan military out of Miraji, but they fear that the Sultan’s plan—which entails blowing up some Mirajin towns that are hosting Gallan soldiers—will have too high a civilian death toll.

So they decide to spark a war between Galla and Miraji, because a war would distract the Sultan and make it easier to kill him, and would also reduce the number of Mirajin casualties.

. . .

I repeat: in order to reduce Mirajin casualties, they instigate a war.

I repeat: because the Sultan will be easier to assassinate if he’s distracted by a war.

Sure, everyone knows that wars don’t actually kill people, and also wartime is when security around a country’s ruler is the most lax and assassins are most likely to succeed.

Sigh.

Amani-Related Things

I’ll just mention two things here, too.

1. Devotion to the Rebellion

Amani (eventually) arrives in the rebellion’s secret headquarters, meets Prince Ahmed, and asks him about his rebellion. He replies (in essence), “I’m all about gender equality and racial equality and democracy and justice.”

The chapter (and his very brief explanation of his cause) concludes:

And thus, Amani becomes a follower of the rebellion, I guess? Is that what “the harder it was not to believe him” means?

I ask this because she seems to be (tepidly) converted without any follow-up questions for him. Without any discussion of how he—and his tiny group of rebels, most of whom seem to be teenagers—intends to take down both the Gallan occupiers and the Sultan himself. Without any snorting at the prince’s naive idealism. Without any skepticism that the prince can in fact bring equality and democracy and justice to what is, by all accounts, a terribly misogynistic and racist culture traditionally ruled by a tyrant.

This lack of critical thinking on her part seems really weird.

Amani then spends some time (days?) floating around the camp and casually picking up tidbits of info about the prince and the rebels, but she never shows a real interest in the rebellion. So I’m surprised when Jin asks her if she wants to officially join the rebellion, and she thinks:

So, uh, she feels a powerful need to be part of the rebellion? Since when? What drives it? Is it the misogyny/gender-equality stuff? Is it Jin? Or is it merely (as she did briefly mention earlier on) that it’s kind of cool knowing that she’s watching history being made?

The reader should clearly understand the protagonist’s reasons for shouldering the responsibility of their goal/mission—and this book seems to have forgotten that very important aspect of storytelling.

2. Amani’s Unrealistic Internal Conflict

This is the one that killed me.

Amani is a total badass, until the rebels tell her she’s a Demdji—the offspring of a human woman and an immortal Djinni father—and they hope to use her magic powers for the cause. Alas, she doesn’t know what those powers are, and even a week under the guidance of other Demdji doesn’t reveal what they could be.

So does she shrug and get back to practicing with her guns, because she already knows she’s got the guts and cunning and skill to be of use to the rebellion? Does she remind herself that she’s the Blue-Eyed Bandit, the best gunslinger in the desert, and an asset to any team looking for trouble?

No. She mopes about how she’s the only Demdji in the world without magic powers, and therefore she’s useless and worthless.

Who is this Amani and what did you do with the other one? I want the other one back.

Fortunately, Jin (who, by the way, is Prince Ahmed’s brother) gets as sick of her shit as I do, and tells it to her straight.

God bless you, Jin.

This could’ve been a genuinely interesting internal conflict for Amani (who otherwise doesn’t have much internal or external conflict going on), if it didn’t come so completely out of the blue—if, for example, she’d been struggling all along with self-esteem issues or concern about her self-sufficiency or her ability to contribute to a team.

But nope. She spent the entire book as a 100% capable and confident badass, until she abruptly decides she’s worthless. Sorry, but realistic internal conflict needs a better set-up than that.

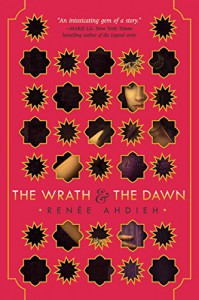

![]()

As far as Middle-Eastern-ish YA fantasy novels go, at least this one didn’t piss me off as much as The Wrath and the Dawn. So that’s good.

But if you’re looking for a vaguely Middle-Eastern-ish fantasy with magic and war and a sexy king, read The Blue Sword.

If you’re looking for a more intense political fantasy that blends Middle Eastern and Western cultures (but on opposing sides of a war, not quite in a unified culture), check out The Lions of Al-Rassan.

If you’d like a spunky narrator whose spunkiness fits more naturally in their (non-modern) culture, maybe try The Thief.

That’s not to say you shouldn’t read Rebel of the Sands; maybe you’d like it better than I did. I just wish I’d spent those hours reading something better.

Hugs,

Liam

1

1

Spoiler Rating: ALL THE SPOILERS, BEWARE

Dearest Ashers,

I’d told you a couple weeks ago that, although The Winner’s Curse wasn’t particularly good, I had hopes for the remainder of Marie Rutkoski’s The Winner’s Trilogy.

And yes, The Winner’s Crime is in some ways an improvement on The Winner’s Curse, but in other ways it’s, uh, quite the opposite.

Prepare yourself for a long and ranty letter.

![]()

I’ve already reviewed the first book in the trilogy, The Winner’s Curse, but allow me to summarize its plot for you here.

Valorian gentlewoman Kestrel impulse-buys young Herrani man Arin, whose peninsula and people had been conquered and enslaved by Kestrel’s father (a famous general) ten years ago. Kestrel and Arin fall in love, but alas! Arin’s organizing a Herrani rebellion, which ends with almost every Valorian in the Herran peninsula dead.

Kestrel’s held hostage/beloved guest on Arin’s estate until, finally, she leaves to tell the Valorian emperor about the Herrani rebellion. At Kestrel’s begging, the emperor grants Arin governorship of the Herran peninsula, on the condition that Kestrel marry his son and heir. She agrees, and—deciding it’s best if Arin think she’s a coldhearted gold-digger angling for empresshood—returns to tell Arin the good news of her engagement and his governorship. Everybody privately angsts.

On to its sequel, The Winner’s Crime.

![]()

Following your heart can be a crime . . .

A royal wedding means one celebration after another: balls, fireworks, and revelry until dawn. But to Kestrel it means living in a cage of her own making. As the wedding approaches, she aches to tell Arin the truth about her engagement: that she agreed to marry the crown prince in exchange for Arin’s freedom. But can Kestrel trust Arin? Can she even trust herself?

Kestrel is becoming very good at deception. She’s working as a spy in the court. If caught, she’ll be exposed as a traitor to her country. Yet she can’t help searching for a way to change her ruthless world . . . and she is close to uncovering a shocking secret.

This dazzling follow-up to The Winner’s Curse reveals the high price of dangerous lies and untrustworthy alliances. The Truth will come out, and when it does, Kestrel and Arin will learn just how much their crimes will cost them.

And oh hey look, we get a map this time!

![]()

General Improvements

I listed a lot of complaints in my review of The Winner’s Curse, including the utter lack of world-building, the unconvincing romance, how passive Kestrel is, and how unrealistic the emperor’s decision was to (1) marry Kestrel to his son, (2) name Arin the new governor of Herran, and (3) allow Kestrel to be the emissary to Herran.

Now I’m giving the author two thumbs up for her attempts to correct (some of) those issues in The Winner’s Crime.

- We learn more about Herrani culture and (in flashbacks) life as a Herrani slave in the first twenty pages of this book than in the entirety of the The Winner’s Curse.

- We’re shown (mostly in flashbacks) significantly more about Arin’s history in this book than in the previous book.

- We’re shown (in flashbacks) actual reasons why Arin fell in love with Kestrel.

- The emperor quickly removes Kestrel from the position of emissary to the Herrani.

It’s like the author read readers’ criticisms about the first book, mulled them over, and applied what she learned to the sequel.

The Romance

Surprisingly enough, Kestrel and Arin don’t reconcile in this book. (Is that cheering I hear? Why yes, I believe it is.) They spend the entire book hurt and angry with each other, and although both want to reunite and clear up the lies and misunderstandings between them, they’re prevented from doing so by numerous situations beyond their control.

And I loved it: their lies, their arguments, their secret hopes. It was beautiful and so painful (in just the right way) to read.

Kestrel’s Crisis

And oh my goodness I loved Kestrel’s struggle between her desire to do what’s right (help the Herrani people) and her loyalty to and love for her father (who’s wholly devoted to the empire).

This is a realistic and heartbreaking dilemma, and definitely raised the book in my estimation

.

![]()

HOWEVER.

Continued Lack of World-Building

Give me more world-building, I’m dying over here.

- What’s the relationship between the emperor, the Senate, and the noble class?

- How powerful is the Senate? What happens if the Senate wants one thing and the emperor wants another?

- Why is everyone in the city betting on the details of Kestrel’s wedding dress? Why does everyone in the city go to one specific bookkeeper to place their bets, instead of the nobles going to a fancy-pants noble bookkeeper, and the middle- and lower-class people going to everyman bookkeepers in their neighborhoods (or neighborhood-equivalents)?

- Can we learn anything at all about the culture of the eastern empire, Dacra? Anything other than “the people wear eye makeup,” “there are canals and tigers around the capital city,” and “the plains to the north are full of nomads”?

- Etc, forever.

World-building continues to be a significant weakness in this trilogy.

Plot Contrivances

I’ll just mention one of the many contrivances that bothered me.

Everyone in the city is placing bets on the color, fabric, design, etc, of Kestrel’s wedding dress, and the winner of the bet will land a fat fortune. For some reason (hint: so the book can have a plot), Arin gets it into his head to ask Kestrel’s dressmaker who has been bribing her for information about the wedding dress. Her answer: almost everyone.

So Arin replies:

Arin then tries to convince his spymaster, Tensen, that this is significant. Tensen’s reaction is basically mine:

(Thrynne, by the way, was a Herrani spy caught trying to eavesdrop on a conversation between the emperor and Senate leader; he was subsequently tortured and killed at the emperor’s orders.)

Arin somehow convinces Tensen to look into the matter of the Senate leader’s bet. And by “convinces Tensen to look into the matter,” I mean “convinces Tensen to convince Kestrel to snoop around about it.”

Through their espionage, they deduce that the Senate leader and the water engineer (who placed an identical bet) have plotted a plot that would harm the Herrani people.

They’re right, of course. But why is Arin so certain the Senate leader’s bet indicated he’d performed a great favor for the emperor? Why is he so certain that the favor involved harming the Herrani people? Why are Arin and Kestrel so devoted to unraveling this mystery, of all mysteries?

I would imagine the palace is thick with mysteries and seeming-mysteries, conspiracies and seeming-conspiracies. Why aren’t they also nosing around a few others that lead to dead-ends? Why didn’t they uncover some “clues” that turned out to not be clues of anything after all?

Their single-minded focus on this one particular mystery, and its perfect payoff in uncovering the emperor’s Evil Plan for Herran, was much too contrived to feel real.

Kestrel’s an Unlikable Idiot

For a character who’s supposed to be (a) sensitive to the plight of servants and slaves, and (b) a cunning and brilliant strategist, Kestrel can be unspeakably bitchy to the people beneath her and consistently fails to consider the possible consequences of her actions.

Both traits are portrayed beautifully early in the book, when her dressmaker (a Herrani woman named Deliah, who is frantically attempting to finish her dress in time for the engagement ball) asks if Kestrel has heard the news:

Dude. Let the poor woman finish pinning a few things to the dress. You already know that the emperor is an Evil Villain who does unspeakable things to the people who fail or disappoint him. What do you think could happen to Deliah if she fails to finish the prince’s fiancée’s dress in time for the ball? Horrible things, that’s what.

But no. Kestrel is too overcome by the prospect of seeing Arin (for the first time in two months) to spare half a thought for a mere servant’s life and well-being.

So off Kestrel runs to meet Arin.

The emperor has repeatedly warned her Hey, I know you love Arin and his people, but you’re going to be empress now, so get your priorities in line. If you so much as blink in Arin’s direction, I can have you both tortured to death.

So what does she do when she hears the Herrani representative has arrived for her engagement ball? She runs barefoot through the palace to meet him, in front of approximately everyone ever, then gets pissy when she realizes Arin didn’t come.

What the hell, Kestrel.

But this isn’t the dumbest (as in holy crap you’re going to get yourself caught what are you thinking) move she makes in the story. It’s one idiotic misstep after another with her, and each one left me aghast.

What’s worse is that the book rarely punishes her for her mistakes.

- Does the entire

palaceempire work itself into a lather over the gossip of her conduct at the Herrani representative’s arrival for the ball? No, it doesn’t. - Does anyone (other than her best friend) notice that Kestrel disappeared from the engagement ball, and when she came back into the ballroom (a few minutes after Arin arrived, his lips swollen and his face smeared with gold makeup) it was with her hair disheveled and her gold makeup suspiciously faded and smudged? No, no one notices.

- Does anyone overhear her when she and spymaster Tensen are talking in a room full to bursting with courtiers and the emperor himself about what their secret spy code will be, and where they’ll meet to share their secret spy information? No, no one overhears.

The list goes on.

Fortunately, she does get punished for two of her (countless) mistakes. Two is better than none, but good god, I was expecting her to get caught every step of the way, and it boggles my mind that she didn’t.

(It doesn’t actually boggle my mind. Of course she didn’t get caught; the book needed her to not get caught until she’d unraveled the emperor’s Evil Plan for Herran. Excuse me while I melt in frustration and despair.)

The Dumb Continues

To continue on the same vein:

When Kestrel and Tensen were discussing where to hold their secret spy meetings while in a room full to bursting with the courtiers and the emperor himself (no, I will never get over this), Tensen suggests they try the only tavern in the city that serves Herrani. Kestrel shoots that idea down, saying that if the tavern serves Herrani, it also serves the emperor’s spies.

HOWEVER.

Sixty pages later, when she’s disguised as a palace maid and conducting her idiotic spy business in the city, she runs into Arin. He recognizes her and challenges her to a tile game; if she wins, he’ll leave the palace immediately (which she wants him to do, for his safety), but ifhe wins, she’ll have to tell him the truth about everything. (He can’t quite accept that she’s the power-hungry courtier she’s pretending to be.)

For some inexplicable reason (*coughsheisanidiotcough*) she consents to the game. He leads her to, you guessed it, the only tavern in the city that serves Herrani.

Remember: Herrani have been the lowest of slaves for the last ten years. They were freed from slavery just two or three months ago. Saying “the only tavern that serves Herrani” is presumably synonymous with “the worst tavern in the city.”

Remember: Kestrel herself dismissed this tavern as a potential Secret Spy Meeting Spot because it’s crawling with imperial spies.

But yeah, sure, the famous empress-to-be (dressed as a palace maid) and the infamous Herrani governor (dressed as himself) go into the tavern to play a game of tiles. The tavern, they discover, is stuffed to the gills, and not just with Herrani:

That’s right. The basest tavern in the city is crawling with nobility and senators. Sure, some high-ranking Valorians might want to go slumming, but not this many.

Nobody recognizes Kestrel or Arin, amazingly enough—even when they stroll in, see that all the tables are taken, and proceed to be as conspicuously rich-and-famous as possible:

Seriously, Kestrel? We’re explicitly told that a palace maid doesn’t make much money. Don’t you think these merchants—or anyone else in the crowded tavern!—will think your behavior is a little unusual for a poor maid?

But wait, it gets worse.

Kestrel and Arin procure a set of tiles to play their game, and proceed to call each other by name and argue IN A CROWDED TAVERN FULL OF COURTIERS AND SPIES about everything that has happened between them. Seriously, look:

(This part of the conversation comes shortly after Arin’s brilliant suggestion that she marry the prince but keep Arin as her lover. Thank goodness she has enough smarts to turn that offer down.)

And do they get caught by any of the dozens of people within easy listening range? By any of the courtiers who should recognize them, or the spies that should perk up at the sound of their names?

No. No, they don’t.

My conclusion: this is so dumb.

A Few Miscellaneous Complaints

This letter is ridiculously long, so let me just mention a few more points:

- We don’t learn the crown prince’s age until page 335; he’s eighteen, but his behavior up to that point had me guessing he was maybe thirteen.

- Both the emperor and the crown prince are painfully flat characters.

- Kestrel spends 95% of the book believing she can’t tell Arin the truth about her engagement, because he’d start a war to break the engagement off if he found out. Then, abruptly, she changes her mind; she writes a tell-all letter and asks Tensen to deliver it. Tensen begs her to think clearly, to which she responds (and this is a direct quote!): “I don’t want to think clearly! I am tired of thinking clearly. Arin should know about me. He should have always known.” BUT WHY, TELL ME WHY. That’s the only explanation she gives, and it’s infuriatingly clear that she only has this change of heart for the sake of a dramatic climax. Authors, please stop making your characters dumb for the sake of the plot.

I need to stop now or we’ll be here all day.

![]()

This book’s earning two and a half stars (instead of two) only because Kestrel’s inner turmoil and the unfulfilled romance were awesome. And hey, at least nobody got almost-raped for the sake of romance in this one!

With love,

Liam

Spoiler Rating: High

Hey Ashers,

The final installment in Marie Rutkoski’s popular Winner’s Trilogy just came out, so it seemed high time I meander down to the library and pick up the first book, The Winner’s Curse.

I mean, come on; a conquered people overthrowing their conquerors? Forbidden love between a conqueror-girl and a slave-boy? A book cover featuring a pretty woman geared for daintily opening letters at prom while clearly in the throes of either physical pleasure or a massive headache? What’s not to love?

Having just finished reading The Winner’s Curse, let me tell you now: there’s quite a bit not to love.

But by god I’m holding out hope for the rest of the trilogy.

![]()

Winning what you want may cost you everything you love . . .

As a general’s daughter in a vast empire that revels in war and enslaves those it conquers, seventeen-year-old Kestrel has two choices: she can join the military or get married. But Kestrel has other intentions.

One day, she is startled to find a kindred spirit in a young slave up for auction. Arin’s eyes seem to defy everything and everyone. Following her instinct, Kestrel buys him–with unexpected consequences. It’s not long before she has to hide her growing love for Arin. But he, too, has a secret, and Kestrel quickly learns that the price she paid for a fellow human is much higher than she ever could have imagined.

Set in a richly imagined new world, The Winner’s Curse is a story of deadly games where everything is at stake, and the gamble is whether you will keep your head or lose your heart.

The plot, in brief: (First 324 pages) Valorian gentlewoman Kestrel, who has grown up on the Valorian-colonized peninsula of Herran, impulse-buys a human being, Herrani gentleman-turned-slave Arin. They’re just getting to the smooching stage of their relationship when Arin and his fellow Herrani rebels poison most of the Valorian colonizers and take Kestrel hostage, thus ending their romance. She twiddles her thumbs in captivity for a hundred pages or so until Something Rage-Inducing salvages her relationship with Arin.

(Last 30 pages) But smooching him is too traitorous for Kestrel’s conscience. She escapes to tell the Valorian emperor that his Herrani slaves have revolted, but begs him not to exterminate them for their insolence. Emperor graciously agrees to establish a suzerain/tributary relationship with the Herrani people, on the condition that Kestrel marry his son and heir (whom she’s never met). She agrees; the Herrani are granted both citizenship into the empire and governorship of their homeland, and Arin (whose faith in Kestrel’s moral character is shaken by her apparent power-hungriness) cries a solitary tear at the news of Kestrel’s imperial engagement.

![]()

Kestrel — the well-bred daughter of the famous Valorian general who conquered and enslaved the Herran peninsula some ten years ago. She’s a poor fighter, but has the makings of a brilliant strategist. Alas, she’s super disinterested in both joining the military and getting married (the only two options available to Valorian citizens), and she shows a scandalous interest in both music and treating her Herrani slaves (almost) like human beings.

Arin — a Herrani slave whose (noble) family was slaughtered in the Valorian conquest ten years ago, when he was . . . nine? Ish? Trained as a blacksmith and farrier, but his true passion lies in music and overthrowing the Valorian government.

Jess and Ronan — siblings, respectable Valorians, and Kestrel’s closest friends. Jess fills the sweet-but-invisible-best-friend role for the book, while Ronan does the sweet-romantic-interest-who-gets-rejected thing.

Cheat — a Herrani man who plays slave auctioneer by day and leader of the Herrani resistance by night. A cruel, petty, jealous, short-sighted brute.

![]()

Well, I’m a sucker for stories about conquered peoples/nations overthrowing (or beginning to overthrow) their conquerors. I think I can trace my suckerhood back to elementary school and Winter of Fire, which is one of those life-changing books that destroyed me in all the best ways as a kid. So two thumbs up for the premise of The Winner’s Curse.

Also neat: Kestrel’s strength is her mind, despite her father’s attempt to make her an elite (or at least competent) fighter. Women who can fight well are awesome, but the fantasy genre’s saturated with them; Kestrel’s disinterest in fighting felt rather novel.

But, uh. That’s about it.

![]()

Bland Writing Style

The writing quality wavered, to say the least. There were some gorgeously written bits here and there, but most of the book was bland, with occasional dips into straight-up bad.

So “glass doors burned with light” is pretty vivid; I love that she “dappled a few high notes over the troubled sound”; and the last sentence was one of the most powerful sentence in the book. But the rest of it is all yawns.

Descriptions of characters’ emotions were generally all right (if bland), but frequently collapsed into the pit of Telling, Not Showing–as we see when Arin learns Kestrel’s attending a dinner party hosted by the villainous Lord Irex:

How does she intuit that the set of Arin’s mouth is determined rather than, say, displeased, angry, annoyed, grumpy, or any of the dozen other emotions that would be likely in this situation? What is it about him that reads as protective? What does protective even look like?

(“Look protective,” I commanded Husband. He gamely cycled through several expressions, without clear success.)

It’s tantalizingly easy to write “There was something about him that looked protective” and be done–but those halfhearted descriptions are agonizingly boring to read. They provide little to no direction for the movies (plays? BBC television series?) I mentally turn books into as I read them.

For my birthday, someone please get me more authors who bother to craft clever, nuanced, imaginative descriptions.

Lack of World-Building

There is an appalling lack of world-building going on here. We’re told:

- the Valorian empire is vast and warlike,

- Valorian society includes an emperor, a massive army, an unknown number of senators (some/many/all of whom twiddle their thumbs in villas far from the Valorian capital, and don’t appear to do anything remotely senate-like), and a noble class that consists of at least one Lord (who wants to become a senator because, uh, reasons),

- the Herrani people live on a peninsula,

- the Herrani once had a wealthy culture focused on arts and stuff, traded overseas with their fancy-pants ships, and were ruled by a monarchy,

- the Valorians blasted through the mountains separating the Herran peninsula from the Valorian empire, overran the Herrani city, and conquered it,

- there’s now a Valorian governor ruling the Herran peninsula, and the Herrani people are enslaved,

- there’s explosive “black powder” which is used in cannons (both on land and at sea), but no hand-held guns,

- there are pianos and violins, as well as printed-and-bound books available in many different languages that families collect in private libraries,

- the Valorian capital is three days’ sailing from the Herrani city,

- and there are “barbarians” causing trouble on the Valorian’s eastern border, somewhere.

Things we are not told include (but are definitely not limited to):

- the name of the Herrani city where the story takes place,

- the physical geography (including size, shape, environment, climate, etc) of the Herran peninsula (where, again, the story takes place),

- the human geography (including any details about culture, population size, demographics, economy, urban/suburban/rural development and spread, etc) of the Herran peninsula,

- anything at all about how the Herrani people now live,

- the name of the Valorian capital city,

- anything at all about Valorian culture, economics, and politics (beyond “they’re not into art” and “they’re big into war”).

We’re not even given enough information about the clothing styles, cuisine, or architecture to paint a half-decent picture of the setting. I mean, sure, the finest Herrani architecture involves marble floors and glass doors and painted ceilings, but that’s as informative as telling us the Valorian women wear silk dresses:not informative enough.

As frustrating as it is to have no clear image of the setting and culture, I was doubly upset about the lack of information regarding the Herrani war, and the Herrani way of life. The book’s plot revolves around a conquered people’s uprising against their conquerors–so shouldn’t we first be shown, in careful detail, how devastating the war was, and how mistreated the Herrani people are now?

But no. We’re told a few times, mostly in passing, that the war was bloody. We’re told in passing that a Valorian’s house slaves now live in communal building somewhere on the property rather than in the Valorian’s house. We’re told in passing that a Valorian can grant their slaves freedom, but it almost never happens. We’re told in passing there’s a market in the city where Herrani slaves (and the very rare free Herrani) sell goods. We’re told in passing that a Herrani who tries to cheat or steal from a Valorian will be whipped.

That’s it.

Arin’s the only Herrani whose life we see in any detail, and his life is exceptional: his mistress is an eccentric Valorian who allows him special freedoms, asks his opinion about things, plays games with him for fun, wants to know him as a person, cares about his well-being. Sure, it’s mentioned (in passing) that he has scars from his hard labor and past whippings, but that’s not enough to provide a vivid portrait of how difficult Herrani life is under the Valorians.

If you want me to be emotionally invested in an uprising, you have to do better than “They’re slaves, and everyone knows slavery is awful, and hey by the way this enslaved young man is super handsome.”

Yes, slavery is beyond awful. But the book didn’t bother trying to show more than a hint of that awfulness, and the story suffered for it.

Unconvincing Romance

Here’s my understanding of Kestrel’s attraction to Arin:

First, Kestrel bought Arin because she was drawn to his strength and quiet rebelliousness on the auction block.

Second, Kestrel’s mind is blown when Arin furiously denies Jess’s claim that the Herrani god of lies must love Kestrel, since Kestrel has such an uncanny ability to discern the hidden truth in things:

The revelation that people might be too afraid to correct her (a Valorian, and daughter of the famous general) if she accuses them of lying has a significant effect:

She’s so shaken that she later asks that Arin always tell her the truth:

But why does she want to know how he truly sees things? Why ishis honesty valuable to her? He’s just a brooding hulk of a blacksmith who glowers at her whenever they’re within line of sight. I don’t understand her motivation for this agreement, and it’s the entire foundation of their relationship.

As for Arin’s attraction to Kestrel, I don’t even know. Sure, she plays the piano and he’s a huge fan of music. Sure, she grants him special freedoms and treats him almost like a human being. Sure, he can empathize with the fact that she feels trapped in her situation: forced to either marry or enter the military, and hating both options. But what else? Anything?

But they fall in love because the book wants them to, I guess, until the Herrani rebellion successfully kills most of the Valorians and imprison the rest. Kestrel’s taken hostage by Arin, and she regrets every kind thought she ever had about him.

Until, that is, a certain Something Rage-Inducing happens (don’t worry, I’ll get there), after which Kestrel and Arin’s seemingly doomed romance is saved–and then Arin undergoes a stunning personality shift, from hulking-brooding-angry dude to hopeful-gentle-sweet loverboy, who eagerly runs up the stairs two at time to see his beloved that much sooner, and jokes with her while they bake pastries, and poetically asks her (his hostage, mind you) to live with him forever:

I don’t know who this Arin is, but he definitely isn’t the same Arin who lurked resentfully throughout the first three hundred pages of the book.

Kestrel’s Passivity

There’s something to be said for a YA heroine who isn’t immediately badass in the face of horrifying adversity (such as seeing her people slaughtered and herself taken hostage by a slave uprising)–but Kestrel’s brand of badasslessness had me in despair.

We’re specifically told that Kestrel’s a poor physical fighter; her strength is in her keen observation and deduction skills, her ability to strategize. Her mind is her weapon.

Yet she makes some unbelievably dumb decisions, such as telling her strong-and-brooding Herrani slave that the entire Valorian regiment is leaving the Herran peninsula, thus leaving the place defended only by the city guard until the new occupying force arrives from the Valorian capital.

And when she’s not being an idiot, she spends most of her time intentionally putting her mind (her primary/only weapon!) on mute, and thus disarming herself:

(Hey Kestrel. You’re probably still a prisoner because you aren’t doing anything about it.)

Is it believable that a young woman in her position might be inclined to try to ignore her problems, let her eyes glaze over and let time pass? Of course. But it makes for an infuriating heroine and an unspeakably dull book. I’d have liked at least a little more emotion in her, more spirit, more action.

Here’s hoping this is part of her character arc across the trilogy–that she makes herself powerless in the first book, realizes the danger of doing so in the second book, and attains true power in the third book. That could make the slog through this first book worthwhile.

Arin’s Character Development

Kestrel spends the book being passive, but Arin’s struggling with the burdens of enslavement, falling in love with the young woman who purchased him, and planning a rebellion.

And it’d make for fascinating reading–if we saw more of the story from his point of view.

We know almost nothing about Arin as a person, except that (a) he’s impertinent and brooding, (b) his family was wealthy before the Valorians came along, at which point he was trained to be a blacksmith, and (c) he loves music.

Arin could’ve been a deep and fascinating character, but we’re shown so little of him and his inner struggles (other than “I want her but she’s Valorian, angst”) that he falls quite flat.

Something Rage-Inducing

Time to put my favorite rage socks on. Ashers, you should probably put yours on, too.

In the Characters section of this letter, I told you about Cheat, the leader of the Herrani rebellion. He serves no purpose in the story except to (a) be a brutal and incompetent leader for Arin to eventually replace, and (b) salvage Arin and Kestrel’s seemingly unsalvageable romance.

Kestrel and Arin’s romance is heading straight to smoochville when the rebellion kills almost every Valorian in the city and Arin claims Kestrel as his war prize (to prevent her from joining the piles of Valorian dead). Kestrel immediately realizes that Arin’s at the heart of this rebellion, and she’s sickened by him and by herself–her blindness to his suspicious behavior, her deep attachment to him. Nothing, it seems, can repair the damage done to their romance.

Until Cheat tries to rape Kestrel.

And Arin arrives just in time to save her.

AAAAAAUUUUGH.

Because rape is a great plot device to use when you need your estranged hero and heroine to reestablish their emotional bond.The best, even.

(That odor you’re smelling is my laptop melting in the face of my fury.)

Whyyyy does it have to be rape? Why does our powerless, passive, captive heroine have to almost be raped for the book’s romance to get back on track? Why couldn’t the author have chosen any other way?

I’m just going to link, once again, to Maggie Stiefvater’s brief rant about the use of rape in literature. And now I’m going to remove my rage socks, breathe, and continue to my final complaint. Which is:

Some Silly Plot Issues

I get the feeling that the author is interested in politics, but isn’t precisely an expert on the topic. Or perhaps she merely assumes her readership won’t notice when political and military things get a little silly in her book.

The most notable silliness comes at the very end of the book, when Kestrel tries to convince the Valorian emperor to grant the Herrani people citizenship into the empire, and allow them to govern themselves. The emperor informs her that doing so would piss off the Valorian senators who live in Herran; Kestrel says paying the senators handsomely might soothe their ruffled feathers:

Uh, what?

- Why does this emperor, whose military already seems feverishly devoted to him and the empire, have to rely on marrying his son to a general’s daughter to “make the military love [him]”? We’ve seen nothing to suggest that his grasp on the military’s loyalty is anything but absolute.

- Why does he need to “distract the senators and their families” with an invitation to a wedding? What threat would the senators pose to him or the empire if he gives governorship of the Herran peninsula to the Herrani, and lavishes the Valorian senators with gold to assuage their hurt pride? How would a wedding satisfy them, if gold can’t?

Also, Valorian society is bursting with gossip about how Kestrel–the eccentric, almost-outcast daughter of the Number One Awesome general who conquered the Herran peninsula–has taken a Herrani slave as her lover and risked her life (and her family’s honor) in a duel to protect him from being whipped for stealing from evil Lord Irex. Even the emperor has heard the rumors, and seems to believe them, as he implies when she initially resists the idea of marrying his son:

Why would he choose her as the future empress?

The emperor’s reasons for forcing Kestrel’s engagement to his son feel flimsy at best. I wish the author had taken the time to show discord and fractured loyalties among the military and senators (not to mention explain what the senators even do, why they exist), to make this decision more realistic (and therefore powerful to me as a reader). Maybe this will come in the sequel?

Kestrel agrees to the engagement, and for some reason (*headdesk*) is allowed to hand-deliver the emperor’s written offer to Arin. She decides to keep the emperor’s ultimatum (“Marry my son or the Herrani will be obliterated”) a secret, and instead tell Arin that she got engaged to the prince because, hell, who wouldn’t want to be empress? Arin feels betrayed by her eagerness to marry someone else, but ultimately agrees to swear fealty to the emperor and become the Herrani governor.

Two issues here.

First of all: why is the leader of the Herrani rebellion (which, remember, killed almost every Valorian on the peninsula) allowed to not only live, but become the Herrani governor? Why didn’t the emperor declare Arin’s execution (or at least imprisonment) part of the agreement, and choose someone less dangerous as the new governor? Placing him as the Herrani leader is the dumbest and most unrealistic decision the emperor could have possibly made.

Authors, stop making your characters unbelievably dumb for the sake of plot. How many times do I have to say this?

Second of all: Arin accepts the emperor’s offer, but with a condition:

Once again I say, uh, what?

The emperor is giving him two options: 1) accept the offer, or 2) see the Herrani civilization exterminated.

Who does Arin think he is, accepting the offer only on the condition that Kestrel is the sole emissary between the Herrani and the imperial court? What power does he have to negotiate? And why does Kestrel say she thinks the emperor would be cool with that condition?

Guys. The emperor believes Kestrel and Arin are lovers. The emperor suspects Kestrel’s loyalties lie with the Herrani people, not the Valorians. The emperor has arranged for Kestrel to marry his son and heir; she’s going to become empress.

Who on earth could possibly believe the emperor would allow Kestrel to have anything to do with Herran, much less act as its sole emissary? And with Arin as its governor?

I swear, if she actually is placed as the emissary in either the second or third book in this trilogy, I’ll cry. I will cry, and it will be ugly.

![]()

I have so much more to say, but I’m giving up. Go read Lizzie’s excellent review now; she covers (more succinctly and elegantly than I could) several other noteworthy points of criticism.

But hey, maybe the sequel will be better? Here’s hoping. It’s lurking on my nightstand now, watching me as I type.

Love,

Liam

1

1

Announcing: Throne of Glass Read-Along

Katie, Ashers,

I’ve made a really dumb decision, god help me. I’m ten chapters into recapping/critiquing the ridiculous (and ridiculously popular) Throne of Glass chapter by chapter, and it is an eye-rolling, rage-filled disaster.

This post—which includes my recap for chapter one—will serve as my one and (presumably) only announcement on Booklikes that the read-along is ongoing on my website. And also my Tumblr. Everyone's free to join the fun.

![]()

“Nothing is a coincidence. Everything has a purpose. You were meant to come to this castle, just as you were meant to be an assassin.”

When magic has gone from the world, and a vicious king rules from his throne of glass, an assassin comes to the castle. She does not come to kill, but to win her freedom. If she can defeat twenty-three killers, thieves, and warriors in a competition to find the greatest assassin in the land, she will become the King’s Champion and be released from prison.

Her name is Celaena Sardothien.

The Crown Prince will provoke her. The Captain of the Guard will protect her.

And a princess from a foreign land will become the only thing Celaena never thought she’d have again: a friend.

But something evil dwells in the castle—and it’s there to kill. When her competitors start dying, horribly, one by one, Celaena’s fight for freedom becomes a fight for survival–and a desperate quest to root out the source of the evil before it destroys her world.

This is my first read-along, so bear with me while I find and don my finest recaps-and-rage socks. It might take a couple chapters.

Direct quotes will either be bolded or put in block quotes. If it’s neither bolded nor in block quotes—even if it’s in quotation marks—I’m paraphrasing.

Let’s do this.

![]()

So a first chapter has two goals: (a) present the protagonist’s chief characteristics, and (b) hint at their impending conflict. Something like Juanita is quiet but stubborn, and has a strong sense of justice, or Charming extrovert Hadia fears she’ll never step out of her totally-perfect sister’s shadow.

Let’s see how Throne of Glass’s first chapter portrays our heroine, shall we?

PARAGRAPH ONE:

After a year of slavery in the Salt Mines of Endovier, Celaena Sardothien was accustomed to being escorted everywhere in shackles and at sword-point. Most of the thousands of slaves in Endovier received similar treatment—though an extra half-dozen guards always walked Celaena to and from the mines. That was expected by Adarlan’s most notorious assassin.

Okay. The jaw-grimly-clenched tone compliments the casual arrogance of the “Adarlan’s most notorious assassin” claim, which—

Wait. If “thousands of slaves” are “escorted everywhere [ . . . ] at sword-point,” and the occasional special assassin snowflake merits seven guards, how many guards does Endovier employ? If I’m doing my math right—let me open my calculator—we’re talking thousands of guards. Sounds like a reasonable use of a kingdom’s military resources.

But back to Celaena, because that wasn’t even the entirety of the book’s first paragraph and already my Ridiculous YA Heroine alarm is wailing.

I’m supposed to believe a teenager is the country’s most notorious assassin, and warrants both shackles and an armed guard of seven to escort her wherever she goes? Come on guys, just give her a Bane mask and strap her to a gurney and be done with it.

So The Most Assassinist of Assassins emerges from the mines after an invigorating day of slavery to find she has a visitor: a man in Ominous Black and a face-hiding hood (someone please tell me how a hood can totally obscure the wearer’s face but still allow them to see out of it, I want to know). The sight of him waiting for her “hadn’t improved her mood.”

That’s it? A creepy dude comes for you after a year of slavery, and all you can say is the sight of him didn’t improve your mood? What about—oh I don’t know—curiosity, fear, surprise, wariness? Could you show any emotion beyond arrogance and badassery?

At least my impending rant about her fearlessness wasn’t necessary. See, she’s only 99% fearless:

[H]er ears had pricked when he’d introduced himself to her overseer as Chaol Westfall, Captain of the Royal Guard, and suddenly, the sky loomed, the mountains pushed from behind, and even the earth swelled toward her knees. She hadn’t tasted fear in a while—hadn’t let herself taste fear. When she awoke every morning, she repeated the same words: I will not be afraid. For a year, those words had meant the difference between breaking and bending; they had kept her from shattering in the darkness of the mines. Not that she’d let the captain know any of that.

“Not that [you’d] let the captain know any of that”? Girl, what makes you think he cares?

Let’s start a list of character traits for fair Celaena:

- Inhumanly badass (allegedly)

- Casually arrogant

- Incurious

- 99% fearless

- Self-absorbed

Charming.

So Chaol Westfall, Captain of the Royal Guard, He Who Looms Skies and Pushes Mountains and Swells the Earth, takes Celaena on a stroll through the mine’s administrative building:

They strode down corridors, up flights of stairs, and around and around until she hadn’t the slightest chance of finding her way out again.

At least, that was her escort’s intention, because she hadn’t failed to notice when they went up and down the same staircase within a matter of minutes.

But an assassin as assassinly as she cannot be fooled:

If she wanted to escape, she simply had to turn left at the next hallway and take the stairs down three flights. The only thing all the intended disorientation had accomplished was to familiarize her with the building. Idiots.

Actually, I agree. If he’s this concerned, why didn’t he blindfold her before tromping her through the entire building?

Celaena pauses her scornful inner monologue to assure the reader that she’s not some dark-skinned uggo—

She adjusted her torn and filthy tunic with her free hand and held in her sigh. Entering the mines before sunrise and departing after dusk, she rarely glimpsed the sun. She was frightfully pale beneath the dirt. It was true that she had been attractive once, beautiful even, but—well, it didn’t matter now, did it?

—which will make a lovely addition to our list:

- Inhumanly badass (allegedly)

- Casually arrogant

- Incurious

- 99% fearless

- Self-absorbed

- Pale and beautiful

Meanwhile, her interaction with Chaol Westfall, He Who Looms (etc., etc.) is just brimming with tension. (Just kidding, it’s not.) She’s pleased by his voice, at least: “How lovely it was to hear a voice like her own—cool and articulate—even if he was a nasty brute!”

- Inhumanly badass (allegedly)

- Casually arrogant

- Incurious

- 99% fearless

- Self-absorbed

- Pale and beautiful

- Snobby

- Judgmental

Chaol asks a question, which she deflects, and his resulting growl launches her into fantasies of his blood splattered over the marble, followed by the delicious memory of “embedding the pickax into [her overseer’s] gut, the stickiness of his blood on her hands and face.”

Naturally, this makes her grin at him.

Celaena: [Grins at him.]

Chaol: “Don’t you look at me like that.” [Moves his hand back toward his sword.]

Whose bright idea was it to put this man—who goes all angry-werewolf when a criminal shrugs off a question, and almost draws his sword when she tries to unsettle him with a grin—in charge of the Royal Guard? He has anger issues and deep-seated insecurity and impending mass murder all over him.

Then it’s Celaena’s turn to ask a question (“Where are we going again?”), not get an answer, and display her resulting anger:

When he didn’t reply, she clenched her jaw.

What’s with these two getting pissed over nothing? It’s like watching two surly, entitled teens who—oh. I get it.

Having covered the basics of Celaena’s personality, the chapter fulfills its second purpose: providing (sledgehammer-subtle) hints of the awaiting conflict: magic has disappeared from the kingdom, and the King of Adarlan has been filling the salt mines with rebels from the countries he’s conquered. (I’ll be so surprisedwhen our heroine becomes the magic-wielding leader of a rebellion that overthrows the King.)

Celaena briefly shudders at the rebel-slaves’ plight, wondering if they’d have been better off dead. But before you go insist I label her “compassionate”:

But she had other things to think about as they continued their walk. Was she finally to be hanged?

Granted, I’d be more concerned about my impending execution, too—but brushing the slaves off with “[b]ut she had other things to think about” is harsh.

Their destination, when they arrive, surprises Celaena:

The [red-and-gold glass] doors groaned open to reveal a throne room. A glass chandelier shaped like a grapevine occupied most of the ceiling, spitting seeds of diamond fire onto the windows along the far side of the room. Compared to the bleakness outside those windows, the opulence felt like a slap to the face.

Because obviously an isolated prison camp/salt mine’s administration building requires an opulent throne room on the off-chance a royal will drop in for a—

On an ornate redwood throne sat a handsome young man. [ . . . ] She was standing in front of the Crown Prince of Adarlan.

I stand corrected.

Chapter Tallies

Just for fun, let’s keep track of how many times some things happen every chapter. Let’s start with:

We’re told Celaena’s A Total Badass: 5

Celaena proves she’s A Total Badass: 0

Celaena fantasizes about murder: 3

Celaena murders someone: 0

Chaol’s surly teen-boy rage: 4

![]()

Our protagonist is unbearable.

1

1

Spoiler Rating: High

My favorite DOCTOR Katie,

First of all: *congratulatory doctoral confetti!* There will be celebrating, and it will beintense.

So I’d gushed to you about Angelfall a while ago, and I’ve finally gotten my grabby hands on the sequel, World After. I was expecting great things for it—but this book didn’t attain greatness. More of a meh-ness, I’d say.

Let me tell you about it.

![]()

Guess I should first refresh your memory about Angelfall.

Human civilization has crumbled after the catastrophic arrival of the (surprisingly cruel) angels. When Penryn’s kid sister Paige is kidnapped by angels, Penryn makes a dangerous move: saving an angel whose wings had just been cut off by the same villains who kidnapped Paige. Her plan is to hold the severed wings hostage until the wingless angel (Raffe) takes her to the angels’ headquarters, where she hopes to rescue Paige.

Penryn, Raffe, and Raffe’s severed wings trek to the angels’ headquarters, where slimy angel Uriel is throwing a 1920s-themed party. Penryn and Raffe infiltrate and save Paige, who’s been experimented on and now seems more monster than human. Meanwhile, Raffe wakes up from surgery with demonic bat wings rather than his own feathered ones. (His nemesis Beliel has stolen and now wears Raffe’s wings.)

In the end, Penryn and monster-Paige are reunited with their mother, but Raffe thinks Penryn’s dead. He disappears in pursuit of Beliel, maybe to never be seen again.

![]()

In this sequel to the bestselling fantasy thriller, Angelfall, the survivors of the angel apocalypse begin to scrape back together what’s left of the modern world. When a group of people capture Penryn’s sister Paige, thinking she’s a monster, the situation ends in a massacre.

Paige disappears. Humans are terrified. Mom is heartbroken.

Penryn drives through the streets of San Francisco looking for Paige. Why are the streets so empty? Where is everybody? Her search leads her into the heart of the angels’ secret plans where she catches a glimpse of their motivations, and learns the horrifying extent to which the angels are willing to go.

Meanwhile, Raffe hunts for his wings. Without them, he can’t rejoin the angels, can’t take his rightful place as one of their leaders. When faced with recapturing his wings or helping Penryn survive, which will he choose?

![]()

World After begins a few minutes after the end of Angelfall, with Penryn, Paige, and their mother being taken into the safety of the human Resistance camp, where they really don’t fit in. Paige ends up running away, and Penryn once again sets off on a mission to save her from the angels—but this time without Raffe.

So, what’s to enjoy about this book?

- The premise continues to be neat: terrifying angels wrecking humanity for reasons unknown—reasons that become (a bit) more known by the end of World After, and which are super interesting, two thumbs up, love them. (Wish we’d learned more, though. Here’s hoping the third book explains everything sufficiently.)

- The writing style is clean and terse and 100% in keeping with Penryn’s voice (she’s the first person narrator, FYI); no overly flowery language that clashes with Penryn’s get-things-done personality and the horrifying situations she finds herself in.

- A tighter focus on Penryn’s family, and how Penryn views/interacts with both her mother and sister.

Okay. It’s time to switch from bullet points to a numbered list, because bulleted lists don’t allow for paragraphs of text. Since there are three things in the bulleted list above, let’s start with Point Number Four in the numbered list below. (You love how I structure my letters.)

4. Monstrosity vs. Goodness vs. Appearance

The theme of one’s appearance doesn’t necessarily correlate with how good or monstrous they are is present in Angelfall, but it’s heftier in World After. We have the good angel Raffe with his sewn-on demonic wings:

There’s evil Beliel wearing Raffe’s beautiful floofy wings:

And, of course, there’s Paige:

Penryn knows Raffe is good despite his devilish appearance, and knows that Beliel is evil even with his beefcake body and new soft wings. The problem for Penryn is Paige; she has a really hard time seeing her sweet little sister in the cannibalistic metal-toothed killing machine that the angels made Paige into. It’s a book-long battle between her sisterly instincts (to protect Paige) and her survival instincts (to keep clear of the monster), and I for one loved watching her struggle.

5. Heroism

Penryn also struggled with the weight of her own morality. This is a cutthroat, dangerous world, but her conscience won’t let her turn away from people in need.

As the story continues, Penryn sort of makes herself responsible for an increasing number of people, until, ultimately, that number is too high to count.

Others view her as a hero for the risks she takes and the good she does, but Penryn sees herself as just a teen doing what she can.

Katie, I love this so much. I’ll never tire of stories about people forced by horrible circumstances to perform acts of grim-and-desperate heroism, but without viewing themselves as in any way heroic. (Correction: I’ll never tire of these stories so long as they’re written at least moderately well.)

6. Romance

There’s not much room for romance in World After; Penryn and Raffe are separated for most of the book, and have very little opportunity to relax and talk when they are together. But the little romantic development we’re shown is delicious. Delicious because it’s not melodramatic or saccharine or earth-shattering. Delicious because it’s quiet and restrained and halting and real.

This is directly related to my praise of the writing style: Penryn doesn’t linger poetically over ever single glance or touch. She acknowledges those brief moments with a succinctness that, for me, reads so much more powerfully than poetic lingering ever could.

Also, this book provides an excellent variation of the Seductive Finger-Licking scene that appalled me in Kiss of Deception. Here’s World After‘s take (in which, I should note, Penryn is not trying to be sexy):

To refresh your memory, here’s how the hot guy (coincidentally named Rafe) responds to the heroine’s (intentionally sexual) finger-licking in Kiss of Deception:

Yeah. No.

![]()

Let’s just stick with the bullet points this time.

- There’s very little dialogue, overall; most of the book is Penryn describing and explaining stuff. This can work sometimes, depending on the narrator’s voice, the plot, the story’s pacing, etc. In this case, it made (the first half of) World After a slog for me.

- The plot “twists” (I don’t even know if they were supposed to be twists) were obvious. Penryn doesn’t know about them, and she’s horrified when they’re revealed, but because I saw them coming I couldn’t share her horror. That’s disappointing.

- Raffe’s semi-sentient sword, which Penryn now carries, sends Penryn its memories of its time with Raffe through dreams and visions. Penryn subsequently learns (a) how to sword fight, and (b) that Raffe has been hunted for thousands of years by demony creatures called hellions. Do the hellions actually make an appearance inWorld After? No. Did trudging through all those dreams and visions feel like a waste of my time? Yes.

- The plot is too similar to Angelfall‘s. Penryn is once again hunting Paige down; she once again gets captured by a large group that she has to escape from; she and Raffe once again infiltrate a 1920s-themed party thrown by Uriel at the angels’ headquarters, that subsequently breaks out into a bloodbath; she once again is reunited with Paige (who, once again, has to use her own new monstrous abilities to help save Penryn); Raffe is once again stuck with his demonic wings (though with more hope this time of getting his fluffy wings sewn back on in the near future). Some key points are different, but too much is the same.

![]()

So overall, World After felt like a weak recycling of Angelfall. We do learn more about the angels’ Destroy Earth campaign, and Penryn is emotionally (as well as physically) reunited with her sister Paige, but nothing else really changes between the end of the first book and the end of this one. As a result, I was mildly bored for most of it.

I’m hoping World After is just a victim of Middle Book of a Trilogy Syndrome (you know, where the second book is just a weird slog while the characters recover from the Traumatic Awesome Events of the first book and the scene gets set for the Traumatic Awesome Conclusion in the third book). If End of Days is as disappointing as this one, I’ll be devastated; Angelfall sets up a really incredible story, and I want the series to live up to that incredibleness.

Hugs,

Liam

2

2

Spoiler Rating: Low-ish

Hey Ashers,

A few years ago, I picked up Leigh Bardugo’s Shadow and Bone, the first installment in her Grisha trilogy. Picked it up, read it, and sold it to a used book store with equal parts disappointment and annoyance.

The trilogy has since become popular, and I’ve been considering giving it another go–and then lo, Six of Crows was released, the first in a new series set in the same world as Shadow and Bone, but involving different characters in a different place and a (slightly) different time. Here was my chance to see if Bardugo’s storytelling abilities had improved enough since Shadow and Bone to make it worth my while to read the rest of the original trilogy.